Fixed income

Bridging the gap: A closer look at the US debt situation

Back to all

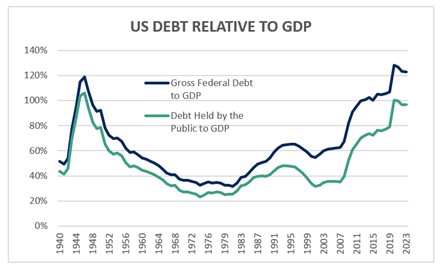

At the beginning of June 2023, a few days before the US would run short of cash to pay all its bills, an agreement was reached between House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and the White House to temporarily suspend the debt ceiling until 2025. In the weeks that followed, the US national debt increased by $1 trillion as the US Treasury replenished its coffers. Today, the total outstanding debt amounts to $32.6 trillion, being 123% of GDP. What’s more, according to estimates from the Federal Reserve, the debt position will increase to $44 trillion, or 150% of GDP, in four years’ time. This led rating agency Fitch to downgrade the sovereign credit grade from AAA to AA+ at the beginning of August. In this article, we will shed some light on the mounting pile of debt, where it comes from, and how it will impact the economy and the financial markets going forward.

Where is all that debt coming from?

What about the creditors?

Should we be worried about debt sustainability?

What is the way out and what are the implications for financial markets?

Where is all that debt coming from?

The historical record of the United States’ public debt traces back to the $75 million debt incurred during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Apart from January 1835, when President Andrew Jackson paid off the entire national debt, the US has always been in debt since its inception. But because of shifts in government spending and fiscal policies, as well as events like wars, economic downturns, and natural disasters, there have been strong fluctuations. US debt relative to GDP levels peaked in the aftermath of World War II, surpassing 118%. In the period thereafter, until the early 1970s, debt to GDP levels came down as we witnessed one of the greatest eras of economic expansion. Eventually, this prolonged period of prosperity came to an end. The large budget deficits during the Reagan-Bush years, the Global Financial Crisis and the subsequent Great Recession, and the Covid-19 pandemic have led to the situation we have today, a colossal debt position of $32.6 trillion. This corresponds to 123% of GDP, even surpassing the post-World War II peak. Harvard University professors Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff stated in their paper “Growth in a Time of Debt” that countries with debt levels above 90% of GDP suffer lower economic growth. A study of the World Bank even lays the threshold at 77% of GDP. Although critics have argued that there is no real threshold for debt becoming problematic, we do recognise that things are not going in the right direction.

Figure 1: US Debt relative to GDP

Source: DPAM, 2023

The US government is still adding to this position. Balancing the budget is a very complex task that requires careful consideration of various economic, social, and political factors. If we take the fiscal year 2022 as an example, the budget deficit amounted to 5.5% of GDP (compared with a 50-year average deficit of 3.6%). The government received 19.6% of GDP in taxes, with more than half coming from taxes on wages, dividends, and interest earned, almost one-third coming from payroll taxes for Social Security and Medicare programmes, and the rest coming from corporate income taxes and some smaller items such as gift and estate taxes. Out of this 19.6% earned, 16.5% had to be spent on ‘mandatory’ benefit programmes whose eligibility rules and benefit formulas are set by law, such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, Income Security Programmes, and Student Loan Programmes. Next to that, 1.9% goes to interest payments on the public debt. This leaves only 1.2% for discretionary items, which over the past 20 years averaged 7.3%. Almost half of it is spent on defence, while the rest goes to health, education, transportation, etc. The result was a deficit of 5.5% for the year 2022, and that year was certainly not exceptional because the US faced a budget deficit in every year since 2001. The biggest part of the spending goes to mandatory items, and as the population ages, these costs will continue to rise. Also, the interest payments on public debt will increase further as the existing debt needs to be rolled over at higher interest rates. And on top of that, discretionary spending will increase due to the growing role of the government in the economy. The ‘Build Back Better’ plan and the ‘Inflation Reduction Act’ are examples of this. The government could address these long-term budgetary issues by reforming the fiscal landscape, but the increasing political polarisation makes this a challenging task. Therefore, for the first time, we are facing budget deficits above 5% outside a recession or a war.

What about the creditors?

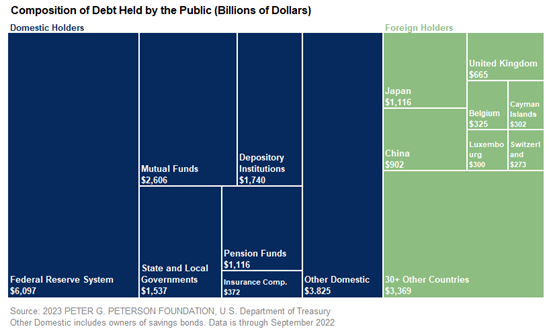

Important to know is who is on the other side of all this debt. Of the $32.6 trillion in debt, 21% is intragovernmental debt, which is simply the result of transactions between one part of the federal government and another. The other 79%, representing debt held by the public (DHBP), is of greater importance as it shows how much has been borrowed from outside lenders through financial markets. Two-thirds of this public debt is held by domestic holders, with the Federal Reserve having the biggest share. Through Open Market Operations (OMOs), the central bank buys and sells securities to move the Federal Funds Rate, i.e. the interest rate that depository institutions charge each other for overnight lending, towards the target established by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Note that the balance sheet of the Fed expanded heavily over the past years as the central bank tried to mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic by purchasing large quantities of treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities. However, with inflation reaching the highest level since the early 1980s, and the unemployment rate reaching the lowest level since the late 1960s, the Fed decided to move from Quantitative Easing to Quantitative Tightening, meaning that their balance sheet started to shrink again. Nonetheless, the Fed remains the biggest holder of US debt by far. Other domestic holders include mutual funds, pension funds, depository institutions, and so on. On the foreign side, investments increased from just 5% of DHBP in 1970 to 49% in 2011 as international investors see US treasuries as a relatively safe investment, with a low chance that the US would ever go into default. Since 2011, the share of foreign investments in DHBP dropped to 30% due to the big investments of the Federal Reserve. Today, Japan and China are the biggest foreign investors.

Figure 2: Composition of debt held by the creditors

Source: Peter G. Peterson Foundation, U.S. Department of Treasury, 2023

Should we be worried about debt sustainability?

Debt is the result of credit, and credit is not necessarily a bad thing because it also leads to buying power. So, without credit, there would be very little development. Consider, for example, how difficult it would be to start a new business if you had to pay for everything with your own assets. However, credit becomes a problem when the money is not put to the best use, and when there is an inability to pay it back. In other words, the money should be used in such a way that it generates sufficient income to service the debt. Unfortunately, history shows that this has not always been the case and that when debt is piling up, the risks for the wider economy start to increase.

Ray Dalio, founder of one of the biggest hedge funds in the world and author of ‘Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises’, studied the cause-effect relationships of the previous debt crises and described the self-reinforcing nature of debt cycles. He explains that on a macro-level, lending supports new spending and investments, which then supports incomes and asset prices, which then makes it easier to borrow and spend more. Eventually, this cycle will reverse, triggering a downward spiral where asset prices fall, debtors encounter repayment difficulties, liquidity dries up, and spending and income levels start to decline. These long-term debt cycles are composed of shorter-term business cycles. Here, each cyclical high and each cyclical low is higher in its debt-to-income ratio than the one before it, until the interest rate reductions that helped fuel the expansion in debt can no longer continue. At this point, the long-term cycle switches direction. Over the last century, the US had two long-term debt crises, one during the boom of the 1920s and the Great Depression in the 1930s, and one during the boom of the early 2000s and the financial crisis starting in 2008. Dalio notes that these debt cycles have existed for as long as there has been credit. Even the Old Testament described the need to wipe out debt once every 50 years, which was called the Year of Jubilee.

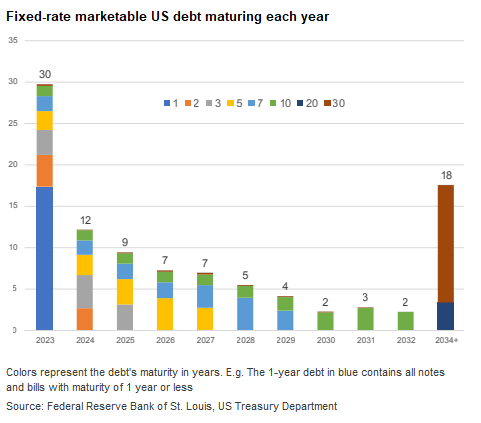

One of the concerns about the US debt position is the amount of interest that will have to be paid. According to Moody’s, the interest expense relative to the total government revenue will increase from 6.8% in 2021 to 10.9% in 2024. In the years thereafter, it could move even higher. This is problematic as we consider levels between 5 and 8% to be appropriate. The FOMC has raised the target interest rate from near zero to 5.5% at an unprecedented speed. Those who issued debt at a variable rate will have to pay the higher interest rates right away, while issuers of fixed-rate debt will only incur the higher costs when the debt matures and needs to be rolled over. Looking at the US debt, we note that around 8% consists of variable rate debt (both TIPS and floating-rate notes), while 68% consists of fixed-rate debt (bills, notes, and bonds). The remaining 24% entails non-marketable debt. What is important to take into account is the maturity profile. Like shown in the graph below, a big part of the debt maturing over the next year is short-term debt, meaning that it has already been rolled over at the higher interest rates that were applicable in the previous months. Therefore, it has less incremental impact on the budget compared to longer-term bonds coming to maturity. Now, based on the split between variable and fixed-rate debt, and the corresponding maturity profile, the CBO projects interest expenses to GDP to increase from 1.9% to 3.6% over the next 10 years. Within 30 years, interest costs will be the largest federal spending “programme”, being more than three times what the federal government has historically spent on R&D, non-defence infrastructure, and education combined. This assumes that the 10Y interest rate gradually rises over the next 30 years but doesn’t go higher than 4.5%, given the slower growth of the labour force, an increase in savings available for investment, and slower growth of total factor productivity. Of course, the longer the interest rates stay high, the more will be rolled over at higher interest rates and the larger the portion of the budget that will go to interest payments. On the contrary, if the Fed succeeds in bringing inflation expectations back to 2% or lower, rate cuts will follow in due time. But even in this case, interest expenses as a percentage of GDP will still likely rise given the projected Debt to GDP outlook. Note that this comes on top of the projected increase in Social Security and Medicare costs as a result of the ageing population and the rising healthcare costs. Therefore, less money will be available to invest in economic growth. Besides that, not only public investments will be crowded out, but we might also see the same for private investments. As the US government will have to compete for funds in the capital markets, they will have to offer attractive interest rates which will divert capital away from private investments, making it more costly for companies to grow their business.

Figure 3: Fixed-rate marketable US debt maturing each year

Source: DPAM, 2023

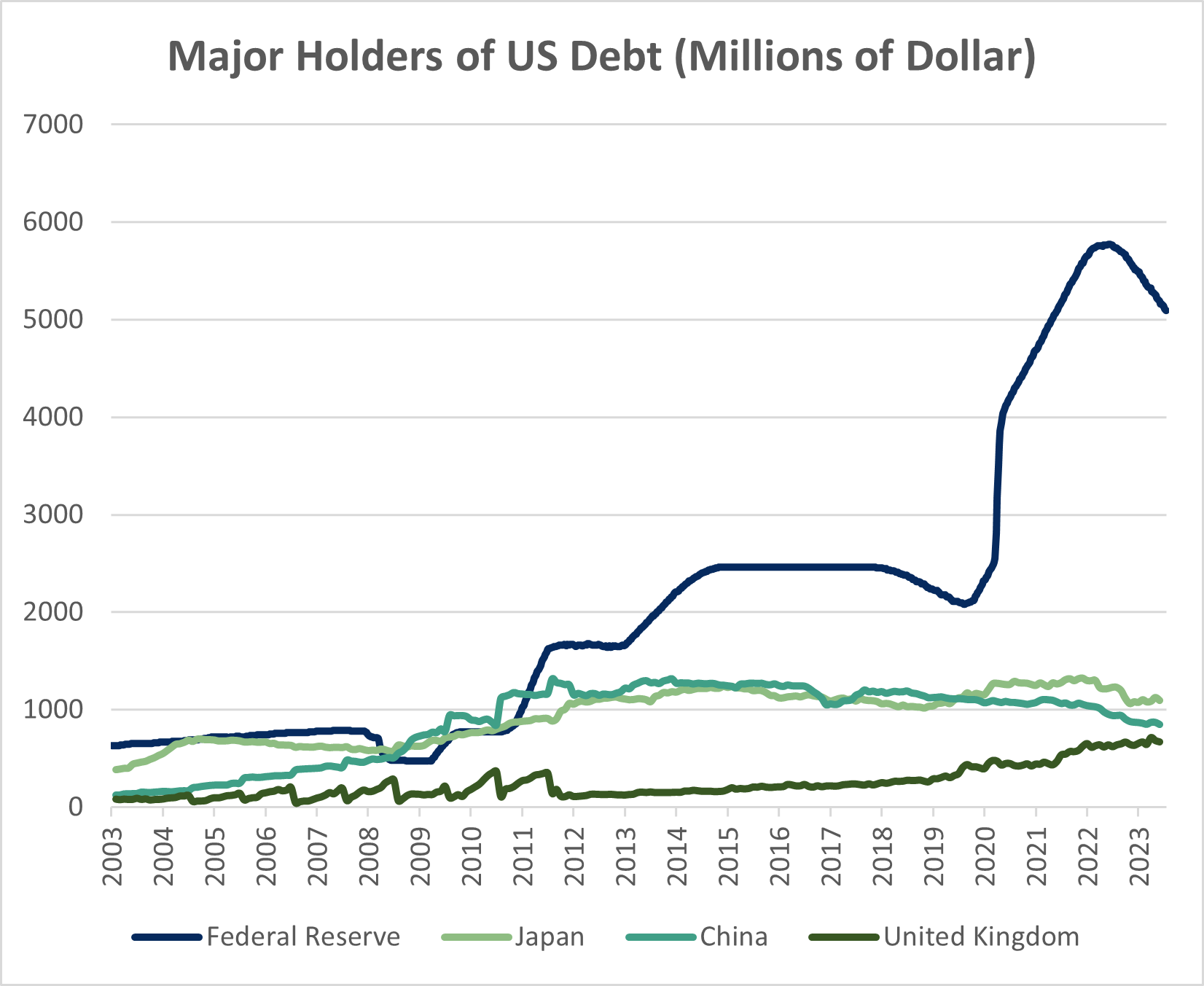

The key question is who will continue to fund this mounting pile of debt. As outlined above, the biggest holder of US debt is currently the Federal Reserve. To mitigate the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the central bank injected substantial liquidity into the system by buying large quantities of US Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities. In doing this, they more than doubled the size of their balance sheet from about $4 trillion prior to the pandemic to nearly $9 trillion at the start of 2022. However, when the non-transitory nature of the high inflation became clear to policymakers, they decided to tighten their monetary policy by raising the target interest rates and by unwinding the massive stimulus programmes. While the former is happening at a historically high pace, the latter is going very slowly. As Janet Yellen said in 2017, the process of quantitative tightening should be like “watching paint dry”, low on drama and low on surprise. The Fed is passively shrinking its asset base by not reinvesting up to $30 billion in maturing Treasuries and $17.5 billion in maturing MBS every month. In September, these caps are set to rise to $60 billion and $35 billion, respectively. This means that the US government will need to find buyers elsewhere until the Fed pivots to an expansionary policy again. Domestic investors, like US pension funds, could fill the gap. However, this would require even higher interest rates, which would again boost the fiscal deficit, leading to even greater amounts of debt. Alternatively, the US government could force banks and insurance companies to hold more of their assets in US Treasuries. This could be part of more stringent capital requirements, where US Treasuries are pushed forward as safe and liquid assets.

Figure 4: Major holders of US debt

Source: DPAM, 2023

Looking at foreign investors, the outlook does not seem much brighter. In response to the Russian invasion in Ukraine, the US weaponised its currency by freezing Russia’s foreign currency reserve of $300 billion. This raised the question for many countries whether they need to re-evaluate their dependency on the greenback. According to figures from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), central banks around the world hold up to 60% of their reserves in the US dollar. This share has been rather stable over the past quarters, suggesting that there is limited impact from the financial sanctions. Possibly, central banks do not find a suitable alternative at this moment. It is true that the US often collaborates with other countries, including those that issue other leading reserve currencies like the euro, the British pound and Japanese yen. Therefore, central banks of emerging countries like Russia, China and India might not feel at ease with holding these currencies. This also explains why we are seeing such strong demand for gold by these central banks. Another alternative that is often mentioned is the Chinese renminbi. However, IMF figures show that it currently represents less than 3% of global reserves, with the Bank of Russia holding nearly a third of all renminbi reserves. The main issue here is that the currency cannot be traded freely as capital controls restrict CNY flows. We have seen the same issues with INR, with Russians struggling to get their money out of India after selling oil denominated in INR. Nevertheless, the potential is to the upside as China is increasingly taking a bigger share in global trade compared to the US. On top of that, countries are starting to use currencies other than the US dollar for doing international transactions, with BRICS already thinking about creating their own currency. Another important thing to watch is the use of petrodollars. In 1973, Saudi Arabia reached an agreement with the US to exclusively accept US dollars as payment currency for its oil. However, Saudi Arabia signalled this year that they are open to discussing oil trade settlements in other currencies as well. These evolutions reduce the reliance of countries on the US dollar and lower the need for their central banks to hold large amounts of the currency in their reserves; hence, it also reduces their appetite to invest in US Treasuries. Also, Japan might be a seller of US Treasuries going forward, albeit for another reason. After nearly three decades of fighting deflation, it seems like corporates adjusted their price-setting and wage-setting behaviours. Given this recent shift in inflation dynamics, the Bank of Japan is slowly loosening its yield curve control mechanism. Due to this, the Japanese yen is expected to appreciate relative to the US dollar, and it could lead to some capital repatriation back into Japan.

So while the US debt position will expand over the coming decades, it remains to be seen who will be funding this. The Federal Reserve is trying to shrink its balance sheet after years of Quantitative Easing, while central banks outside the US have less rationale to hold the greenback now that its share in global trade is falling.

What is the way out and what are the implications for financial markets?

The first and the most obvious step is to stop the bleeding. In other words, the US government should reduce its yearly deficit as much as possible. One way of doing this is to increase its revenues. Many countries have introduced or increased consumption taxes in recent years to fill their coffers. As the US is still lacking a national consumption tax, this could be one of the options to consider. Another option could be to increase the number of taxpayers by welcoming more immigrants. As they often arrive as young adults who are ready to work and don’t need any education, it is considered to have a positive fiscal impact. In any way, there is a strong need for meaningful, long-term fiscal reform. To overcome last-minute political battles on the debt ceiling, Congress could create a bipartisan commission consisting of an equal number of Democrats and Republicans who are working together on fiscal reform and debt reduction. Next to focusing on the revenue side, they should also take measures to reduce spending. A reform of the healthcare system has a high priority here, given that the Medicare Board of Trustees expects the programme to become insolvent in 2031. Another option is to increase the retirement age, which will have a positive impact on both the revenue side and the cost side of the budget. Of course, all these measures will not happen overnight. No meaningful reforms are expected before the start of the next presidential term in 2025. Moreover, a re-election of Biden or Trump would not really move the needle as neither of them has announced specific plans on reducing the debt position.

Although the Federal Reserve acts as an independent central bank, they are still accountable to the public and to Congress. When there is a substantial shortage of demand for US Treasuries, the Federal Reserve will be under pressure to step in. This would mean the end of Quantitative Tightening, and the end of their balance sheet normalisation. In theory, the Fed could buy as many government bonds as they want. However, there are practical limits and considerations to keep in mind. Firstly, excessive market dominance could lead to concerns about their independence, lower credibility, and therefore lower liquidity. Secondly, by injecting more money into the system, they run the risk of pushing inflation higher. This would not be a problem when the economy is contracting, and when inflation levels are subdued. But looking at what’s ahead, there are multiple factors leading to the expectation that the natural state of inflation will be structurally higher than before, such as climate change and deglobalisation. If this indeed results in higher inflation, it will be very challenging for central banks to run an expansionary monetary policy. Therefore, the central bank will have to strike a balance between using their tools to achieve their dual mandate of price stability and maximum sustainable employment, while also maintaining stability and credibility in the financial system. If we revisit Ray Dalio’s book ‘Navigating Debt Crises’, it is written that the right amounts of stimulus are those that a) neutralise what would otherwise be a deflationary credit-market collapse and b) get the nominal growth rate above the nominal interest rate by enough to relieve the debt burdens, but not by so much that it leads to a run on debt assets. A potential tailwind would be a jump in productivity growth, as this could help to keep inflation under control while increasing the money supply. Artificial Intelligence might be the holy grail if it becomes a ‘General Purpose Technology’, being a technology that affects a wide range of applications across different industries and sectors (comparable to inventions like electricity, the internet, etc.). Today, we are already seeing numerous investments in many different areas, such as healthcare, customer service, agriculture, and manufacturing.

Historically, there has been a strong correlation between market liquidity and the performance of equity markets. Based on this, we could expect that when the Federal Reserve returns to Quantitative Easing, the additional oxygen that is pushed into the system will send market valuations higher. But when the Federal Reserve would not be able to fill the gap, the US government will need to rely on the private sector, such as mutual funds and pension funds. For them to be incentivised to buy US debt, the interest rate will need to be attractive enough. This would be negative for equity markets, as the earlier-mentioned crowding-out effect would, ceteris paribus, result in higher interest rates for corporate lending. In turn, this would result in a smaller difference between a corporate’s Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) and its Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), also known as the Wicksellian Spread. It gives an indication of the attractiveness of starting a new business or project. A smaller spread, due to either a lower projected return or higher borrowing costs, will not only lead to lower profitability but also discourage the demand for new credit. If this happens in combination with the above-mentioned austerity measures for keeping the budget deficit to a minimum, it would be a double whammy on corporates’ earnings.

To conclude, the US debt situation is reaching critical levels. Studies from Reinhart-Rogoff and the World Bank mention lower economic growth when a country surpasses a threshold of 90% and 70% Debt/GDP respectively. Over the next four years, the level is expected to increase to 150% of GDP. Factors such as the higher level of interest rates, an ageing population, and an insolvent healthcare system will only exacerbate the challenge of reducing the debt burden. It also remains to be seen who will be funding the US government. Foreign countries, who often have similar debt problems themselves, will have less appetite for US treasuries when the US dollar becomes less prominent in global trade. The Federal Reserve could pivot their objective of balance sheet normalisation and run an accommodative policy again. This would boost asset valuations but might threaten price stability in the longer term. Alternatively, they could attract private investors by offering higher interest rates. However, this could spill over into the corporate market, putting a burden on economic growth. What is most important for now is that both the US government and the Federal Reserve build a long-term plan where fiscal and monetary policy are aligned, living apart together.

Disclaimer

Degroof Petercam Asset Management SA/NV (DPAM) l rue Guimard 18, 1040 Brussels, Belgium l RPM/RPR Brussels l TVA BE 0886 223 276 l

Marketing Communication. Investing incurs risks.

The views and opinions contained herein are those of the individuals to whom they are attributed and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other DPAM communications, strategies or funds.

The provided information herein must be considered as having a general nature and does not, under any circumstances, intend to be tailored to your personal situation. Its content does not represent investment advice, nor does it constitute an offer, solicitation, recommendation or invitation to buy, sell, subscribe to or execute any other transaction with financial instruments. Neither does this document constitute independent or objective investment research or financial analysis or other form of general recommendation on transaction in financial instruments as referred to under Article 2, 2°, 5 of the law of 25 October 2016 relating to the access to the provision of investment services and the status and supervision of portfolio management companies and investment advisors. The information herein should thus not be considered as independent or objective investment research.

Past performances do not guarantee future results. All opinions and financial estimates are a reflection of the situation at issuance and are subject to amendments without notice. Changed market circumstance may render the opinions and statements incorrect.