Multi-asset

The hidden cost of monetary debasement

Back to all

Monetary debasement has been a recurring process throughout economic history, with governments and central banks seeking ways to manage mounting debts and economic crises. In its simplest form, debasement refers to the reduction in the value of a currency, historically through lowering the precious metal content (such as gold and silver) in coins, and in modern times through excessive creation of money. While these measures have sometimes provided short-term relief, they carry hidden costs that can have profound long-term implications.

Monetary debasement throughout history

Monetary debasement, that is, reducing the value of money by increasing its supply, has repeatedly led to economic turmoil throughout history. In the Roman Empire, emperors diluted silver coins with cheaper metals like copper to fund military and economic expansion, which eventually caused inflation, disrupted trade, and led to social unrest. Sometimes, citizens contributed to debasement by shaking coins in a bag to wear down the edges, collecting the metal shavings to mint new coins. This practice became so common in 17th-century England that the authorities had to replace the entire money stock in what became known as the Great Recoinage. A more recent example can be seen in post-World War I Germany, where the government printed excessive amounts of money to pay war reparations. This triggered such hyperinflation that, by 1923, the amount of money that could buy 100 billion eggs in 1918 was barely enough to purchase a single egg.

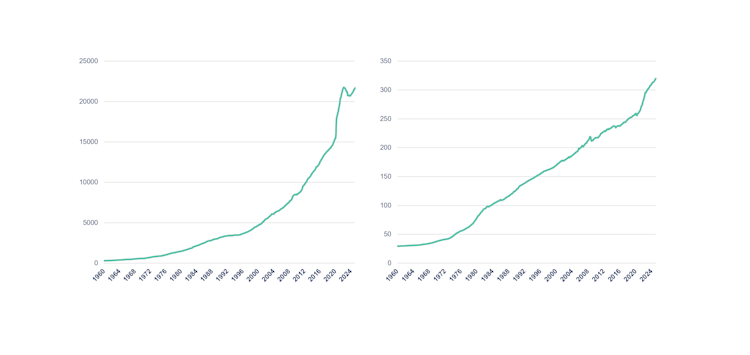

Monetary debasement remains highly relevant today. The M2 money supply has been growing at an exponential rate, while purchasing power continues to be eroded by both monetary inflation and the rising cost of living. Many believe this is a direct result of excessive money printing by central banks. However, the true creators of money are commercial banks, which create money out of thin air every time they issue a new loan. Central banks influence the reserves held by commercial banks, as well as the rates at which banks lend to each other, but the actual level of money creation will ultimately depend on the risk appetite of commercial banks. To some extent, governments can also be seen as money creators, since they transfer central bank money to the private sector by running fiscal deficits, also known as debt monetisation. Here, the link to central banks’ balance sheets is more direct, with the Federal Reserve being by far the largest holder of US debt. This has become more pronounced since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, which was followed by a significant expansion of central bank balance sheets:

The Federal Reserve (Fed): Increased from under $1 trillion in 2008 to over $6.89 trillion by 2024.

The European Central Bank (ECB): Grew from approximately €1.5 trillion in 2008 to over €6.43 trillion in 2024.

The Bank of Japan (BoJ): Expanded from ¥100 trillion in 2008 to over ¥748 trillion in 2024.

The Bank of England (BoE): Increased from £78 billion to £851.6 billion.

People’s Bank of China (PBoC): The PBoC’s balance sheet more than quadrupled, reaching approximately ¥44 trillion by the end of 2024.

Despite this amount of money creation, inflation in the following years remained quite low. This is often used as an argument to say that the two are not related. However, given the weak state of the economy and the deflationary forces at play (such as private sector deleveraging and the energy revolution), we believe that these measures may have prevented the biggest fear: deflation. If prices were to fall, the real value of government debt and the debt-to-GDP ratio would rise, and tax collection would be negatively affected. Normally, people’s purchasing power increases through higher salaries, which the government can tax. But if people get more purchasing power from falling prices, the government cannot take its share. This is one reason why governments prefer inflation: it reduces government debt, lowers the debt ratio, supports the financial system, and creates opportunities for more tax revenue.

US M2 money supply (USD, billions) [left]

US consumer price index [right]

Source: DPAM, Bloomberg; 2025

Unsustainable debt and its impact on monetary policy

With the US government currently sitting on a debt pile of almost 100% of the US economy (approaching World War II levels), investors are growing concerned about the long-term sustainability of this debt. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the US debt-to-GDP ratio could rise to 115% within a decade and even reach 181% in 30 years. To assess the situation, one has to look at three factors: nominal GDP growth, the primary deficit, and the interest costs the government must pay on its existing debt. A rule of thumb is that for debt to be sustainable, nominal GDP growth minus interest expenses must be greater than the primary deficit. This would mean the government has money left to pay down its debt. As this is not the case today, there is a risk that bond markets see no end to this and lose their confidence in the US government, which could cause interest rates to spike, further intensifying the government’s debt burden.

Given the many budgetary challenges faced by the US government, it seems unlikely that politicians will be able to reduce deficits significantly in the coming years. This raises the question of how the Fed can affect the situation. To keep debt under control, it is best to have low interest rates. This would limit the government’s borrowing costs and also encourage higher nominal GDP growth. However, helping the government manage its debt is not the responsibility of the central bank, and in fact, would go against its mandate of ensuring price stability, since lower rates could lead to higher inflation. This has raised concerns about how independent the Federal Reserve can remain from the US government. As mentioned earlier, the Fed is the largest holder of US debt, and a collapse of the system is something it also wants to avoid, given its dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability. So, it may also be in the Fed’s interest to prevent the debt from spiralling out of control. In 2020, the Fed announced a change to its policy, adopting a Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) framework. Previously, the Fed aimed to maintain inflation at a steady 2%, but the new objective was to have 2% inflation on average over a longer (unspecified) period, allowing for times when inflation is temporarily above target. However, after experiencing unusually high inflation in recent years, one might expect a period of inflation below 2% to balance the average, yet it appears this policy has quietly been set aside.

The question now is how long bond buyers will tolerate rising debt levels and the resulting loss of capital. In 2022, the announcement of unfunded tax cuts by Liz Truss caused UK bond yields to spike, the pound to fall, and eventually led to emergency action from the Bank of England. Because the US treasury market is much larger, this sort of event is less likely to happen as quickly in the US, but it cannot be entirely ruled out. In 1978, the US dollar nearly lost its status as the world’s primary reserve currency when it fell so sharply that the US Treasury had to issue bonds in Swiss francs. In just four years, inflation reached 50%, gold rose 500% and Paul Volcker had to raise rates to 20%. Such an event could happen again if monetary debasement goes too far and investors lose confidence, triggered, for example, by a downgrade from credit rating agencies (as seen in 2023), or a failed treasury auction. These events may not cause an immediate collapse, but as Ernest Hemingway put it, it can happen “gradually, then suddenly”. To gauge how bond markets are feeling, one can monitor the relationship between US bond yields and the US dollar. If yields rise while the dollar falls, it is a warning sign. This is what happened in the weeks after President Trump announced his retaliatory tariffs on Liberation Day. Even if tariffs are later reduced through negotiation, the damage is done: the US is seen as an unreliable trade partner, even by its closest allies, and that will have a negative impact on the global trade done in US dollars. What is also concerning is the way Trump is pressuring Jay Powell, the Chair of the Federal Reserve. While Trump cannot legally fire Powell, repeated threats could harm central bank independence and further accelerate monetary debasement. Given that Powell’s term ends in 2026, we believe the transition will be managed in a market-friendly way, with Powell’s authority gradually and quietly passed to a newly appointed, more dovish president.

Going beyond fiat: from gold to Bitcoin.

These long-term cycles of accumulating and eventually writing off debts have existed for thousands of years, and have profoundly affected the performance of investment strategies. Since 2008, loose monetary policies such as prolonged low interest rates and quantitative easing have exacerbated these effects, forcing investors to adapt their portfolios in order to preserve real wealth and maintain purchasing power. Across asset classes – from fixed-income and equities, to gold and the rise of digital assets such as Bitcoin – the impact of monetary debasement is both significant and vital for successful investing.

The distinction between equity and fixed income is also important in this context. While equity represents ownership and a claim on a company's real earnings (as businesses can sometimes protect against inflation by passing rising costs on to consumers), fixed income involves contractual obligations to receive cash flows in nominal terms. Holding debt during the later phases of the long-term debt cycle is considered riskier, as inflation erodes the real value of future payments. The large amount of outstanding debt increases the likelihood of default and eventually leads to inevitable debt and currency devaluations. In low-interest-rate environments, the real yields of these assets often turn negative, making them unattractive as a store of value. However, fixed income remains a cornerstone of institutional portfolios, playing a crucial role for pension funds, insurance companies, and sovereign wealth funds that require predictable cash flows to match their liabilities. In addition, government bonds serve as a critical tool for financial stability and monetary policy. Inflation-linked bonds, such as Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), offer some relief as their payments are linked to the difference between expected and realised inflation. Overall, we believe that equities are a better option for preserving real wealth during periods of monetary debasement, although fixed income still provides diversification and stability.

With traditional assets like equity and fixed income under pressure, the focus turns to alternative havens such as gold, real estate, art, and digital assets like Bitcoin. Gold has long been regarded as a traditional safeguard against monetary debasement, maintaining its role as a store of value during times when fiat currencies weaken. However, the rise of digital assets such as Bitcoin has introduced a new and disruptive alternative to gold's historical dominance. While gold supply can change with mining output, Bitcoin’s fixed supply of 21 million tokens is immutable, governed by its underlying blockchain protocol, making it the hardest asset in the world. BlackRock’s iShares Bitcoin Trust ETF (IBIT) achieved record-breaking success by reaching $10 billion in assets under management within just seven weeks of its launch, signalling a major shift in how it is viewed and used by multi-asset portfolio managers.

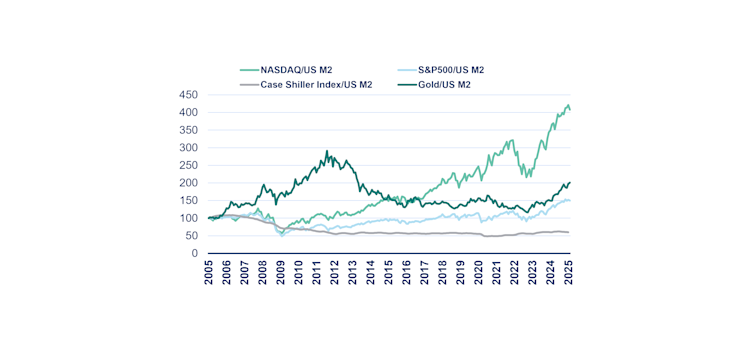

Asset performance adjusted for US money supply

Source: DPAM, Bloomberg; 2025

One way to look at the impact of monetary debasement is to value financial assets against the M2 money supply, which reveals their real performance. Over the past 20 years, the Nasdaq – the tech-heavy equity index – has been comfortably leading the pack, benefiting from strong, secular technological tailwinds (such as, internet, cloud computing, and now AI). Gold comes in second, showing its strength as a traditional store of value. Real estate has been the biggest surprise, as its slower price growth has not kept up with the rapid increase in money supply.

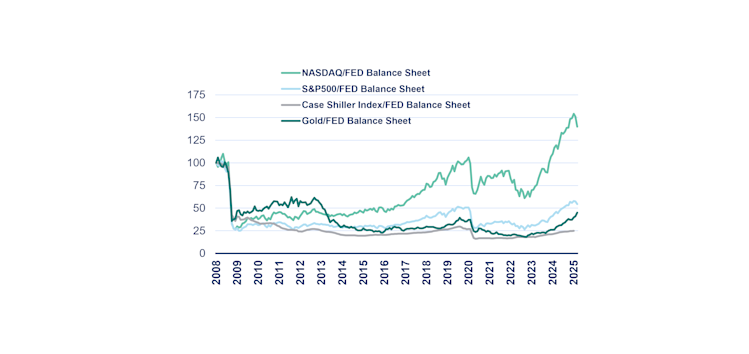

Asset performance relative to fed balance sheet

Source: DPAM, Bloomberg; 2025

If we shorten the time frame to the period after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and use the Federal Reserve balance sheet as a measure – given its important role in expanding the money supply – the results are less encouraging. It is striking that technology stocks (and digital assets) have been the only assets to outpace the growth of the balance sheet. Both the S&P 500 and gold have struggled to act as effective hedges against monetary debasement, while real estate has fallen further behind in real terms.

Given the low likelihood of governments balancing budgets through spending cuts or tax increases, it is almost certain that they will try to reduce the debt burden by keeping interest rates below inflation, allowing nominal growth to exceed the cost of debt. As currencies lose value, some assets become more attractive as stores of wealth. In a time of large-scale money creation and fiscal irresponsibility, this leads investors towards alternative assets such as inflation-linked bonds, gold, commodities, real estate, and digital assets like Bitcoin. Looking further into real assets, alternative stores of value including fine art, collectibles, or other items with intrinsic value, can also help protect against monetary debasement.

In conclusion, monetary debasement remains a complex issue, where central banks and governments must choose between continuing policies of debt monetisation – risking long-term currency debasement – or pursuing fiscal austerity, which can slow growth and cause social unrest. Whether through the rise of alternative assets such as gold and cryptocurrencies, or through reforms to the global monetary system, the world must find a way to address unsustainable levels of debt and the threat of monetary debasement. In the meantime, the lesson from history is clear: unchecked debt monetisation and monetary debasement lead to economic instability, inflation, and eventually, the collapse of currencies. The question is not whether these policies will have consequences, but when and how severe those consequences will be.